The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was launched in 1932, just as Hitler was beginning his own ascent into power. It was led by Sir Oswald Mosley, an establishment figure with an aristocratic background who had served as an MP for both the Tory and Labour Parties. (German and Rees, p. 198). The BUF gained much support from the lower middle classes in areas such as Hackney and Stoke Newington from people who resented the growth of large Jewish communities in these areas. As well as this, the BUF also gained support from figures such as Lord Rothermore who owned the Daily Mail. In January 1934 a Daily Mail headline read: ‘Hurrah for the Blackshirts.’ (German and Rees, p. 198).

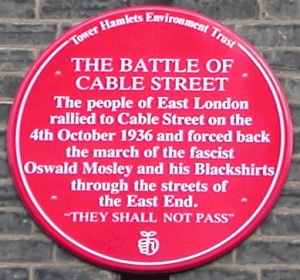

The BUF held an enormous fascist rally in 1934 at Olympia. 5,000 demonstrators led by the Communist Party disrupted the rally in protest. (German and Rees, p. 198). This rally took place before the Public Order Act of 1936 which banned the wearing of political uniforms in any public space or meeting and required the permission of the police for political marches to take place. A great deal of violence ensued in which black-shirted fascist stewards beat up anti-fascist hecklers. As well as this, in 1936 a Fascist march at Cable Street in Stepney was met with 100,000 protestors who succeeded in preventing the black-shirts from passing. These events sparked huge debates over the legitimacy of dissent and protest in public politics and the role of the police and law at political meetings and demonstrations. Lawrence argues that, ‘ultimately the reaction against fascist violence led to a significant increase in the state’s role in this traditionally private sphere of political life.’ (Jon Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) It is worth analysing in more detail then because it is relevant to the theoretical study of social movements.

The pretentious Mosley proclaimed The Olympia meeting to be the largest indoor meeting ever held with an audience of 15,000, and used an audacious array of lighting and mass speaker systems. (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) Jon Lawrence argues that ‘many of the most interesting aspects of the Olympia controversy were less about the rights and wrongs of fascism than about where to draw the line between ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ behaviour within democratic politics. To what extent should politicians tolerate disorder and organized protest as part of the rough and tumble of popular politics, and how should they go about controlling the excesses of the political crowd?’ (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) Mosley fully believed in and condoned the mobilisation of huge private forces. However, this was considered intrinsically ‘un-British’ and after the Battle of Cable Street a political consensus emerged which allowed the Public Order Act to be passed. Lawrence argues that up until this point, politicians and the public had ‘balked’ at the using of police to maintain order at indoor political meetings. (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) This is because at the time, the nature of political meetings and peoples’ reactions to political violence were very different.

During the Edwardian and Victorian period, force within politics was widely accepted. Rowdiness and disruption at political meetings was common place. Lawrence explains that as late as 1908, ‘Sir George Radford (Liberal, Islington East) described political disorder as “a form of sport which was as well recognised as football”; while Will Thorne (Labour, West Ham) simply argued that if they wanted to stop disruption “It was for those who organised the meetings to make proper provision”’ (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) People felt that they had the right to speak out at political meetings and it was widely accepted, that the political party who held the meeting, would mobilise their own stewards to deal with any trouble. The police were in complete agreement on this issue. Such a culture though, played a direct role in the birth of Mosley’s para-military BUF. However, Mosley had not picked up on the change in attitude towards such behaviour that was occurring, and this would ultimately lead to the downfall of his black-shirts. Lawrence confirms: ‘An important factor in Mosley’s failure was his refusal to recognize that political sensibilities had hardened against disruption and disorder in the years since the First World War.’ (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) Although, this was eventually recognised by Mosley, the threat of Fascist violence, and the chaos of the Cable Street Riots all led to a political consensus that favoured the increase of state regulation in British politics. (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.)

Despite official leaders of the labour and Jewish movement being against militant mobilization against the black-shirts, the Communist Party, the Independent Labour Party and some elements of the Jewish ex-servicemen’s organisation and the Jewish youth were prepared to resist the blackshirts, and on October 1936 they assembled a mighty 100,000 protestors to flock Cable Street. (German and Rees, p. 198.) Although not all of the leaders of leftist movements were entirely ‘United’ in their their goal, Bill Fisherman, who was a member of the Labour Youth League, commented that the mobilisation ‘seemed like an act of solidarity because, on the same day, the Republicans in Spain were also preparing to defend Madrid against General Franco’s nationalist forces.’ (German and Rees, p. 199.) The crowd that assembled considered themselves ‘United’ and certainly represented themselves with ‘Numbers’ worthy of a united social movement. Protestors were carrying banners proclaiming ‘No Pasaran’ which was the slogan taken from the Spanish Republicans which meant, ‘They shall not pass.’ (German and Rees, p. 199.) This symbolic use of ‘repertoire’ is evidence of the Left aligning itself together, making connections between each others ‘claims’ and identifying a common enemy. Fisherman recalls further:

‘The tension rose and we began chanting, “One, two, three, four, five! We want Mosley dead or alive!” and “They shall not pass!” Mosley encountered his first setback from a lone tram driver. About 50 yards away from me at Gardiner’s Corner, I saw a tram pull up in the middle of the junction — barring the Blackshirts’ route from Aldgate to Whitechapel. Then the driver got out and walked off. I found out later he was a member of the Communist Party. At that point the police charged the crowd to disperse us. They were waving their truncheons, but we were so packed together there was nowhere for us to go.”’ (German and Rees, p. 199.)

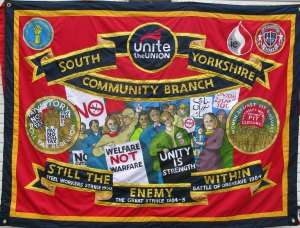

The police continually charged at the crowds with significant use of force in an attempt to disperse the anti-fascist protestors, but failed to do so. The Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Philip Game, directed Mosley and the fascists to go through Royal Mint Street and Cable Street but the communists used loudspeakers to direct their own crowd and form more barricades which the police simply could not dismantle. Violence continued to escalate and eventually the police had to instruct the blackshirts to abandon the march. This defeat is widely considered to be the beginning of the end of Mosley and his blackshirts. (German and Rees, p. 200.) It is important to note that all of Charles Tilly’s social movement criteria applies to the BUF as well. They had their own repertoire and elements of WUNC. What is interesting though is how the movement failed after laws were put in place that prohibited the actions of their repertoire. Like any successful social movement, the BUF’s repertoire worked in accordance with their aims and objectives. The reason Mosley was so pro political-violence was because, ideologically, fascism, will not tolerate political dissent. Their repertoire had to contain elements of intimidation, and violence because their ‘claims’ were to completely overhaul political freedom and democracy. When they were no longer able to apply such tactics, the movement lost any sense of purpose and deteriorated.

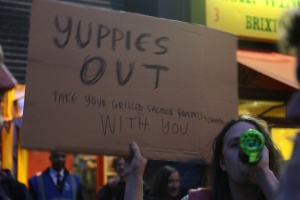

Although due to time constraints this issue will not be covered in much depth, but the importance of space and place is essential here. The BUF battled for control of public space in the east end of London. Both sides, Communist and Fascist, ‘thought explicitly in terms of the conquest or defence of ‘territory’, conceptualizing their struggle through the metaphors of war.’ (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) When the BUF announced plans to step up its East End activities in the summer of 1934, it openly acknowledged that the ‘Reds’ would be ‘very annoyed at the invasion of the East’, because for years they had ‘looked upon [the district] . . . as their own’. (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) The blackshirts were almost trying to claim back territory that they claimed had been lost to Jewish communities. The space itself was the object of the ‘claim’ that the movement was making. Contentious politics tend to take place in urban social spaces because they are a resource, not only to mobilise ‘numbers’ in, but they serve as a site in which symbolic activity can take place and ‘communities of interest’ can develop in particular areas which cultivate groups with collective ‘identity claims.’

The Cable Street Riots took political violence onto the streets on a massive scale, and many feared that it posed an immediate threat to public order. (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) People were aware of the brutal street politics that were taking place on the Continent and did not want it at home. As a result, Lawrence states that ‘most on the Left were prepared to accept tougher controls on political meetings and demonstrations in return for sweeping legislation to limit fascist activities on the street.’ (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.) Organisations could no longer form para-military wings and the fascists right to march had been curtailed. As well as this the Right won tougher powers to control political disruption and public protest in general. (Lawrence, pp. 238-267.)

It was after Cable Street then that the state had an increased role in controlling public protest. The 1936 Act stated that police permission was needed for a march to take place. This is an extremely significant historical moment. Michael Lipsky claims that, ‘police may be conceived as street-level bureaucrats who represent government to the people.’ (Michael Lipsky, p. 78) With this in mind, the police with power to control public protest, can enforce a particular agenda for the government. Such changes in legislation came about as a response to the real threat of militant fascist violence. Such a threat no longer exists and so, it could be argued that the excessive amount of police force and state control over political demonstrations these days, which includes an enormous amount of surveillance and information gathering which is used for the purpose of sabotage and the restriction of resources, is an encroachment of peoples constitutional rights of freedom of speech and rights of expression and is therefore unconstitutional and undemocratic. Allyson MacVean and Peter Neyroud back this point up explaining how the Public Order Act of 1936 led to the Public Order Act of 1986 which ‘introduced greater measures to control disorder from demonstrations and protests.’ (MacVean and Neyroud, p. 91.) ‘The 1986 Act requires protest groups intending to march or protest to give notification to the police at least six days in advance of the event taking place, allowing the police to prohibit or place conditions on the event… It is only with the authority of the Secretary of State that the police can prohibit a march.’ (MacVean and Neyrou, p. 91.)

It is worth remembering this when studying any form of protest because if the targets of a movements ‘claims’ are the government, then they have to consider the extent of how much the state will control and shape the nature of their own protest. Repertoires, in order to be effective, have to take these facts into consideration, and be formed in ways that can avoid excessive state control. This is why the study of culture is essential to social movement theory, because it can be an effective way of bypassing conventional forms of protest that the state has tight control of.